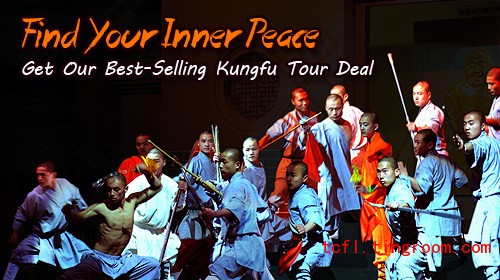

“Kung Fu” means hard work, or skilled effort, and was originally used in reference to the demanding years of practice that were necessary to achieve mastery of a style. Over the years, Chinese martial arts have been known as ch’uan fa (fist arts), kuoshu (pronounced “gwo-shoo”, it means “national arts”), Chung-kuo ch’uan (Chinese boxing), wu kung (effective use of martial force), ch’uan shu (fist arts), and wushu (fighting arts), the last made popular during China’s ascending Communist Period (1949-1071). In Shaolin etiquette, therefore, the style and the term “Kung Fu” is likely linked as a single entity, as in “Tiger gung fu” or “Wing Chun gung fu”.

There can be little doubt, after examining firsthand the structure of Kung Fu, that mastery of it is indeed mastery of a fine art form. It requires a tremendous amount of background, in the way of both tacit and demonstrated skills.

The priests of old were adept in: medicine, music, art, weapon-craft, religions, animal husbandry, cartography, languages, history, and of course, gung fu. The artist had to be more than a fighting machine, he had to know how, where and why to enter a fight, and even of greater importance, how to avoid conflicts.

The power of the Kung Fu practitioner lay in his ability to defend himself against apparently impossible odds and situations. After years of diligent practice, Shaolin monks became more than simply adept at the ways of survival.

As youngsters, the applicants for priesthood were made to do the most basic and difficult work related to the upkeep of their temple. Their sincerity and ability to keep the secrets of the order were severely tested for years before the finer aspects of the arts were revealed to them. But, upon being accepted by the elders of the Temple, entry into gung fu practice was to open fantastic new views. Students would work long hours training mind and body to work together in a coordinated effort. They would learn the principles of combat, the way of the Tao, and the Buddhist lessons, and together these teachings would ensure the student’s way to peace.

Within the Temple, priority was given to training in unarmed gung fu. In principle, any weapon can be taken from a practitioner and used against him. Superior knowledge of unarmed combat includes extensive training in disarming opponents. For this reason, the forms of Shaolin are generally referred to as “kuen” or “fist sets”.

During the first six months to one year of gung fu, a student would only learn the wide horse stance. The stance training not only strengthened their legs, but encouraged concentration and perseverance, absolute essentials before martial arts techniques would be trained. Students who failed to master the stance, or cut corners on training were dismissed from the temple, for it is a Shaolin belief that “all strength starts with a solid foundation”.

The next phase involved learning basics of eye and hand coordination. Under the supervision of a disciple, students would learn to make and throw a proper straight fist. Shortly thereafter, students would be given access to a set of three stout bamboo poles, on which were protection targets.

This training would also last about six month, and would be supplemented with learning additional stances, basic stance walking, and a few simple blocks. Only after these basics were well ingrained could a student begin working on the first kuen.

The choice of when a form would be taught, which form would be taught, and which version would be taught would be the supervising master’s alone. After evaluating the student and conferring with teaching disciples, the master would either offer a general form or, for more gifted pupils, a basic form in one of the styles.

General forms came from simple Choy Li Fut, Black Crane, the generic Five-Formed Fist sets, or a non-Temple style. The goal in teaching a general form was to give a student additional material with further subtleties of movement and combinations so that a further evaluation would be possible.

Some students would never move into one of the elite styles, and though they would continue to train in gung fu, would not typically be considered candidates for eventual master’s rank. Some were encouraged to join other orders.

Contrary to popular belief, these forms are not taught as preparation for actual combat (in which an opponent is an unpredictable variable) but as ways to increase speed and transition from one technique to another.

Forms normally have three levels and versions. The basic level, taught with moves that may be extremely general or merely difficult; an intermediate level, in which more of the true meaning and subtlety of the moves is revealed; and the advanced version, which the masters themselves practice.

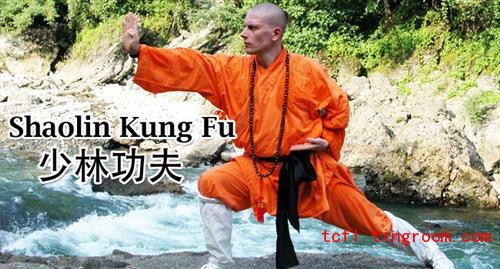

Upon completion of the student stage, the practitioner became a disciple, who would be taught the higher secrets of the arts and philosophies. Use of weapons of all descriptions would be taught as weapons of attack and defence. The monk would perfect his movements to coincide with his breathing. Lessons aimed to meld the mind with the realm of meditation known as mindlessness. From this training students would learn to harness their ch’i.

Ch’i is the power governing life. Only by harnessing such energy can a person of mild stature learn to break bricks with their bare hands, or learn to sense the movements of an opponent in the darkness.

Essential to movements in gung fu are ch’i-controlled actions. The essence of ch’i-controlled action may be illustrated by comparing a karateka with Kung Fu stylist. The karate movements are principally linear, hard, and distinct from each other, while gung fu moves often follow circular paths, look soft and graceful, and blend subtly into each other.

Kung fu techniques have few clearly distinct “start” and “stop” points.

Ch’i, properly coordinated, allows for fluidity. Consider a single drop of water. Alone, it is harmless, gentle, and powerless. But what on earth can withstand the force of a tsunami? The concept of ch’i is the same. By tapping into the universal energies, one increases one’s abilities manifold. How can an opponent damage a gung fu practitioner when he is unable to strike and injure a body of water?

English

English Japanese

Japanese Korean

Korean French

French German

German Spanish

Spanish Italian

Italian Arab

Arab Portuguese

Portuguese Vietnamese

Vietnamese Russian

Russian Finnish

Finnish Thai

Thai dk

dk